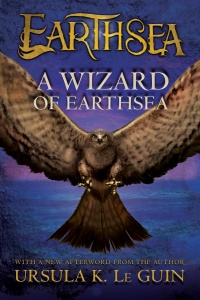

Reading Notes returns! This month, I’ll be looking at assorted books by Ursula K. Le Guin, beginning with A Wizard of Earthsea.

Reading Notes returns! This month, I’ll be looking at assorted books by Ursula K. Le Guin, beginning with A Wizard of Earthsea.

A Wizard of Earthsea was first published in 1968, following a couple of earlier short stories that were set on Earthsea but did not contain the main characters of the central series. It’s even earlier than McKillip’s Riddle-Master of Hed trilogy, and I’m curious about the history of high fantasy and whether Earthsea is the first enduring series written by a woman. (I don’t have the background knowledge to say whether this is true or not, but I’d be curious to hear from others if you have any sense.) It’s in fact so surprisingly early that I found myself wondering to what extent Le Guin was actually influenced by Tolkien. (I assume she must have been to some extent, and yet LotR didn’t really hit the US full-force until the mid-1960s.)

I first read this book in 2007 (having a handy searchable list of my reading for the past 10 years is SO nice). Although I loved it then and continued to think of the series as one of my favorites, I’m not sure I have ever re-read at least this first book! Because of this, I was both interested and a little worried about my reaction; sometimes going back to books you loved can be a mistake.

In this case, it wasn’t. Le Guin is a marvelous writer and it’s interesting to read this story with a more adult mind. I certainly think I caught more of what she was trying to do than before.

Part of what made the reading experience so interesting are the tone and prose style A Wizard of Earthsea is written in. It’s a slight book, and it covers a lot of chronological ground. The story actually begins with the land, situating us physically and geographically. I don’t think this is an accident; while Ged is important to the story, he is also treated with detachment and clear-sightedness. Le Guin also writes the story in a heightened and at the same time tightened prose style. It’s the kind of epic language which can go wrong very easily, and which has–possibly because of this–definitely fallen out of fashion. Le Guin, like Tolkien, can pull it off. But unlike Tolkien, her prose has the sense of not a single word being used unnecessarily. This isn’t meant as a dig at Tolkien, but they are writing different stories with different aims.

One of the other things A Wizard of Earthsea does share with Lord of the Rings specifically is worldbuilding where there’s a sense of things that we don’t entirely see. Le Guin references but does not always explain the mythology of the Archipelago, the festivals and rituals, the poetry and epics. I love this; if there’s a failure of modern worldbuilding I think it’s often to over-explain. I’m curious to know how much Le Guin had worked all of this out for herself. With Tolkien, of course, we know: the publication of The Silmarillion, and The Book of Lost Tales, and the Unfinished Tales, etc has made the mythology known. But here what we have is that same feeling I remember reading Lord of the Rings for the first time: a depth of culture and history and mythology that I don’t understand but that is real and felt throughout the book.

But Le Guin is not in any way simply writing in response to Tolkien (to whatever degree she was). In fact, I found it really fascinating that A Wizard of Earthsea is so self-contained; the focus on the wizards, on the use of power, on one very flawed and human protagonist all give it a flavor that is wholly its own. It’s also very lacking in references to real-world events. While the question of the use and dangers of power is a relevant one, it’s always relevant; I wasn’t tempted to read in it a particular reference to contemporary events. (Contrast this with L’Engle, for instance, who is writing very much out of her particular historical moment.)

Perhaps the most important thread running through A Wizard of Earthsea, the theme to which Le Guin returns over and over again, is the idea of magic as power, but also danger and potential destruction. Ged’s struggle in the first quarter or so of the book is with his own power and his pride and reliance on it. Because it is not enough, in Earthsea, to simply be powerful. You have to understand your power; you have to approach it with humility. One of the first and hardest lessons that Ged learns is the limits of power: of mages’ power in general, and of his own. Early in the book we hear “that which gives us the power to work magic, sets the limits of that power. A mage can control only what is near him, what he can name exactly and wholly.” Le Guin’s magic has rules, although they are not always strictly logical ones, and the wrongful use of that magic brings destruction.

Ged starts off the book as incredibly flawed–if he were a female protagonist, the reviews would be full of the word unlikeable. He is stubborn, he is proud, he is envious and resentful, he is sure of himself and his superiority to everyone else. The narrator even says, “for the most part he was all work and pride and temper.” It’s only when he calls up the shadow that he is confronted by his own lacks, but even then he overcorrects into a hesitance to use his power even when he should.

He’s also, after this point, curiously without agency. Not entirely, but throughout the central portion of the book, he is mostly running from his shadow, his past, and himself. Only about 50 pages from the end, when he has returned to Gont and Ogion does Ogion tell him: “If you go ahead, if you keep running, where you run you will meet danger and evil, for it drives you, it chooses the way you go. You must choose. You must seek what seeks you. You must hunt the hunter.” It’s not enough to simply have the knowledge of power. You also have to choose how you will direct it, and at the same time that choice becomes constrained because there are things you are simply not willing to do. The Master Summoner on Roke alludes to this earlier when he says, “…the truth is that as a man’s real power grows and his knowledge widens, ever the way he can follow grows narrower: until at last he chooses nothing, but does only and wholly what he must do”

And so, in the end, Ged does what he always had to, and what he never could have guessed: by “naming the shadow of his death with his own name, [he] had made himself whole: a man: who knowing his whole true self cannot be used or possessed by any power other than himself.” Le Guin somehow manages to write about this really complex and deep theme in a way that’s balanced between explication and mystery. I ended the book thinking that I couldn’t really tell anyone what had happened, but I felt it very clearly. It’s perhaps most apparent in this image of balance that keeps showing up throughout the book. Vetch sings about it just after Ged’s last encounter with his shadow: “Only in silence the word, only in dark the light.” It’s in the tension that runs through Ogion’s words that I quoted earlier, and in the balance of power and lack of choice that the mages follow.

I am pretty awed by Le Guin’s ability to successfully write about these really complex topics while also writing Ged’s journey in this masterful, crystalline prose. At the same time, this isn’t an entirely perfect book, and I felt its lack most notably in the treatment of women. I believe that the series as a whole doesn’t stay here, and Le Guin is a writer I generally think of as pretty feminist. And yet–I can’t ignore the pattern in this book which is that not a single woman aside from fourteen-year-old Yarrow is treated with kindness. Women’s power is scorned while the women themselves are shown as envious, terrifying, and out to steal Ged’s power for themselves. Not to mention the fact that Roke doesn’t admit women to study there at all! I think it’s likely an unconscious pattern, but it’s pretty clearly there and I did feel I had to mention it.

Despite this, I am really glad that I decided to re-read this book; it’s rich and subtle and complex, and absolutely deserves its status as a fantasy classic.

Book source: personal library

Book information: 1968, Parnassus Press; fantasy (might be pubbed YA now?)

14 replies on “Ursula Le Guin Reading Notes: A Wizard of Earthsea”

Great essay! I really need to read this series again, or at least the first two books of it (I never could quite warm to THE FARTHEST SHORE, but maybe now that I’m older I’ll appreciate it more as LeGuin intended).

Thank you for this! You’re very right about the treatment of women here – I’d reread recently (OK, 2013 – here’s my review: http://alibrarymama.com/2013/08/23/a-wizard-of-earthsea/ ) and didn’t continue with the series because of the sexism, though I remember rereading the whole series lots as a kid. But reading it then means I never read the more recent books, and I know she addressed some of these issues later on.

Does that mean you never read Book 2, THE TOMBS OF ATUAN? Because that book is *all* about women, with a diverse cast of distinctly drawn female characters with their own perspective and ambitions and scarcely any male characters at all except for Ged, and while I felt that LeGuin didn’t follow through on that particular story the way she could and should have (by the time TEHANU, which is a militantly feminist book by contrast, came along it just made me angry because it seemed like too much, too late), TOMBS is a book I’ve read and loved over and over again. I just sort of… have to make up my own future for the heroine after the end of that book, instead of settling for LeGuin’s.

No, I did read Tombs of Atuan… just so long ago that I’d forgotten what was in it when I listened to A Wizard of Earthsea three years ago, and was too frustrated to continue. Perhaps I’ll see if the audiobook is checked in right now…

I love other books by le Guin, but I was never a fan of this series.. I really should give it another chance!

I haven’t read the Earthsea series, although I’ve loved LeGuin’s Hainish novels.

Yeah, I read The Wizard of Earthsea a few years back — I’d never read anything by Ursula K. LeGuin! — and didn’t, honestly, love it. I wasn’t enthused to read The Tombs of Atuan, even though I’ve been told that it has more ladies and niceness in general.

I loved the Tombs of Atuan, but (like RJ Anderson says above) had to make up my own ending. It’s the only one of the Earthsea books I really got into. Have you tried any of her other books?

It’s interesting to me to hear of people not having read Earthsea or not liking it, because to me it was seminal; Narnia was my childhood country, and Earthsea I discovered in adolescence. I think you never outgrow those books. But I’ve also reread the series more than once, and it has never disappointed me.

LeGuin wrote an interesting essay about her journey as a writer into feminism, and how these books were written when she didn’t even realize how informed (or, rather, misinformed!) she was by the culture of the time (1968, remember!). Tehanu is her attempt to correct the entire world view of the series, and I agree it doesn’t quite work (though I enjoyed the book and thought it was well done), but I do love the way she manages to expand and reshape her whole mythology—she has a deft hand at worldbuilding.

[…] For myself, I have whole stacks of books, though I realize I might be in the middle of slightly fewer than usual. I’m listening to A Plague of Bogles by Catherine Jinks in the car, reading Winter by Marissa Meyer in print at home and Under a Painted Sky by Stacey Lee at work. I’m actually reading books from my list that I put together in January and feeling all proud of myself! That doesn’t mean I’ve been able to resist the siren call of other books that have come across my radar. I have The Ultra Fabulous Glitter Squadron Saves the World Again by A.C. Wise up next in print – I just couldn’t resist that title. (Note that it is most definitely an adult book, just based on the first page.) After that will come Something like Love by Beverly Jenkins, as I’d been feeling like a romance and just discovered that she is a Detroit area author who specializes in heavily researched African-American historical romances. Color me sheepish but intrigued. I checked out her next oldest title, to give the latest one a chance to get a little more exposure on the new shelf. I think I read just one review of Rebel of the Sands by Alwyn Hamilton, where it might have been compared to The Blue Sword by Robin McKinley, one of my all-time favorites, and that was enough to convince me to check it out on the spot. I’m continuing my reading of Hilary McKay’s older books with The Exiles at Home. And in reserve on audio is The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula LeGuin, which I haven’t read since childhood but which R. J. Anderson (geeky thrills! Conversations with authors I admire!) encouraged me to give a second chance to over at By Singing Light. […]

[…] Reading Notes returns! This month, I’ll be looking at assorted books by Ursula K. Le Guin. The first post on A Wizard of Earthsea, is here. […]

[…] I’ve already talked about A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula Le Guin Voices by Ursula Le Guin Sorcerer to the Crown by Zen […]

[…] Ursula Le Guin Reading Notes: A Wizard of Earthsea (2016) […]

[…] posts about Ursula K Le Guin: Planet of Exile (2011) Gifts (2011) Lavinia (2011) Reading Notes: A Wizard of Earthsea (2016) Reading Notes: The Tombs of Atuan (2016) Reading Notes: Voices […]